In October 2022, I was playing a routine tennis match when my knee went crunch. This is part 2 of the story. You can read part 1 here.

Getting the diagnosis

Once WPA had authorised me to see Dr Cath Spencer-Smith, who is one of my favourite sports doctors, I contacted Cath’s secretary and got booked in to see her in her clinic at the Shard. In the session, we talked about how it had happened, and she got me to demonstrate some movements and then examined my knee. The egg-shaped swelling on the outside of my knee was looking particularly impressive and appeared to be typical of a meniscal cyst. I couldn’t squat down fully and my knee wouldn’t straighten well either, so we agreed that an MRI scan would be the next step. I called WPA after leaving Cath’s clinic, and they agreed to authorise it.

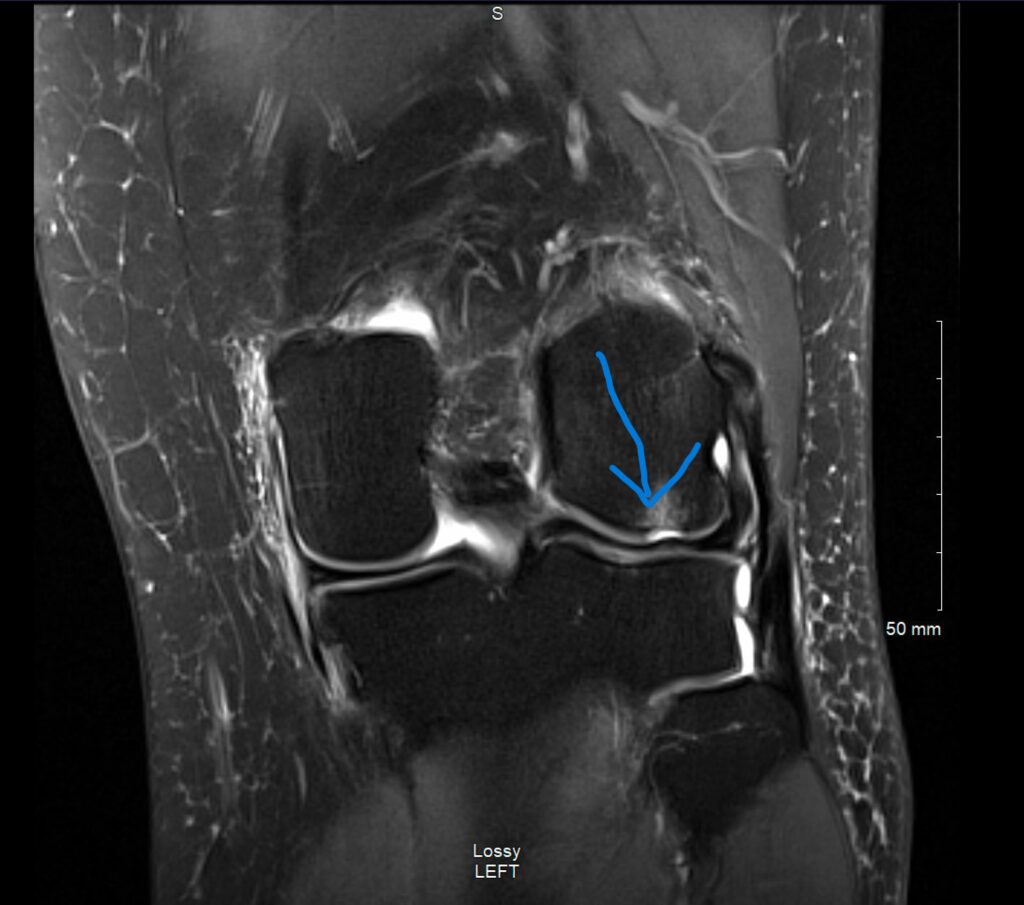

I had the 3T MRI at Old Broad Street the following week, and was able to get a follow-up with Cath over Zoom to discuss the results. Sharing her screen, she showed me the knee from the side. I couldn’t see a definite tear in the meniscus, which looked promising, though the bottom of the femur bone looked a bit bruised.

Then she showed me the image of the knee from the front, and I realised why the femur looked bruised. It wasn’t the meniscus. The end of the femur, like the end of most bones, is covered in a thick layer of articular cartilage. Most of the end of my femur was well covered, but there was a hole, right in the middle of the cartilage that covers the outer side.

This is called a chondral (cartilage) defect. It wasn’t what I’d hoped or expected to see, but it did make sense. Bare bone is sensitive and leaky, which explained both the pain and the swelling – and why it didn’t seem to be healing.

A trip to see the surgeon

My go-to surgeon for chondral defects is Ian McDermott. The thing about surgeons (and physios and medics in general) is that you never want to have to go and see one; but luckily I’ve been around the London orthopaedic scene for a fair while now. I texted him and he was able to look at my scan; and although he’s a busy man, he managed to fit me in to have a look at my knee and discuss its internal workings.

Ian pointed out that the location of my chondral defect was a particular problem for a tennis player, because it’s exactly where I weight bear in 30-45 degrees of knee flexion. If you ever play or watch tennis, that’s the position a player will aim to adopt when waiting for and when hitting a ball. So if I wanted to play again, then I would definitely need surgery. But it’s also a position you have to get into when you’re going up and down stairs, and doing all sorts of things, so if I wanted to avoid surgery, it would be pretty limiting.

Surgical options

Ian explained that there’s a spectrum of possible operations that he offers to patients with chondral damage:

- The smallest possible operation is an arthroscopy – keyhole surgery – to smooth off the ragged edges of the articular cartilage. This wasn’t going to be appropriate for me, because the edges of my chondral defect were quite clean and not especially ragged, so it wouldn’t achieve much or change my symptoms.

- The next level is nano-drilling. This is also keyhole surgery. In this operation, the surgeon uses tiny, needle-width drill bits to drill up through the hole into the bone itself. This makes the bone leak blood and bone marrow into the hole, where it forms a scab which eventually forms a type of cartilage. The operation has about an 80% success rate at the 5 year point. It’s similar to an older operation called microfracture where they bash the bare bone with a tiny awl to make it leak; but Ian feels nano drilling is less traumatic to the bone.

- The third level is cartilage grafting. This is open surgery, so you end up with a bigger scar. They take a sample of cartilage and essentially grow a patch of your own cartilage in a petri dish, then staple it into place with biological darts to hold it on. Again, there’s about an 80% success rate at the 5 year point.

- The fourth level is to use an Episealer – essentially using a metal plug, with a polished surface. The plug goes into the bone, and the polished surface fills the hole, neatly dovetailing with the remaining biological cartilage to form a continuous cover for the femur. This causes more damage to the bone than the first three levels, but less damage than having a knee replacement. This is a relatively new operation, so we don’t yet know how long an Episealer implant lasts.

- The fifth and sixth levels are partial and total knee replacements, where you remove some or all of the ends of both the femur and the tibia, and put metal caps on them. The average knee replacement lasts for 10-15 years, so you don’t want to do that in someone aged under 50 unless it’s absolutely vital, although as I’ve mentioned before, you tend to get better results with a biological knee replacement which is 3D printed to match your own shape, than with a standard-shaped one.

Surgical plans

Ian felt that the nano-drilling was the right level for me, based on my age (under 50) and level of activity (I play tennis at a fairly high level, including county and military veterans’ matches and ITF Seniors tournaments when I can make the time, and have no plans to stop) and the size of the defect. This means that if I do need further surgery in a few years’ time, I will have minimal bone damage from this operation, so it will be easier to “upgrade” me to one of the higher levels.

Although nano-drilling sounds like a small operation – and it isn’t massive in the grand scheme of things – the recovery is long. The plan is for my bone to leak and form a scab inside my knee, and for that scab to form cartilage on which I can weight bear. That process takes months and during that period, I’ll have to be careful not to damage the scab in any way, as it could disrupt the healing process and potentially cause the surgery to fail.

So – I will be on crutches for at least 6 weeks after the op, followed by reduced impact and weights for at least 6 months. That’s going to take some planning and some prehab…