Over the next few weeks, I’m planning a series of posts on the ways that different body parts can go wrong, and what do to about them. However, before I do that, I think it’s important to understand how muscles in general work. Did you know that there are (at least) three types of skeletal muscle? And that they are designed to behave in very different ways? If not, then read on…!

Not all muscles work in the same way; and as clinicians, we physiotherapists like to separate them out into groups, so that we are better able to predict their behaviour. The first muscle classification system appeared in the literature in 1972, and researchers have been refining it ever since. I’m a fan of the three-part model proposed by Comerford and Mottram in 2001, and this underpins the way we look at muscles in my practice.

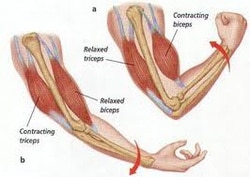

At one end of the spectrum are the power muscles, the prime movers. These are long, bulky muscles whose job is to move the trunk and limbs. They are full of fast-twitch fibres which provide power more than endurance – like your biceps or quads, which help you to carry shopping bags and sprint for the bus. They’re superficial muscles – on the outside of your body, so they’re the ones you can see when you stare into the mirror at the gym.

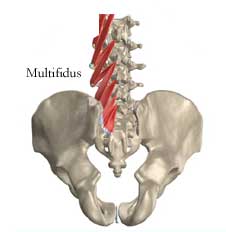

At the other end of the spectrum are the postural muscles, the local stabilisers. These are tiny muscles right next to the joints, whose job is to support your ligaments and control your joints so that the bones don’t shear or slide about when you move. This means that you should always be weight-bearing through the middle of your joints, which are designed for loading. They are full of slow-twitch fibres which are built for endurance – so that you can keep holding yourself upright and not collapse by lunchtime. They also have an interesting property called the feedforward mechanism, which means that it’s their job to pre-empt movement. So, just before you lift your arm or your leg using your prime mover muscles, your brain sends a signal to the local stabilisers, telling them to switch on to protect your joints.

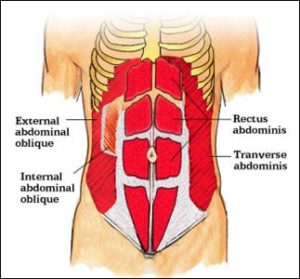

In the middle of the spectrum are the global stabilisers. These are (mostly) built more like sheets than ropes; and they generally sit between the local stabilisers and the prime movers. They have some properties of each type of muscle: a more even mix of fast-twitch and slow-twitch fibres. Their job is to switch on after the local stabilisers, but before the prime movers.

In an optimal situation, the sequence runs this: you decide to move, your brain sends a signal to your local stabilisers to make sure your joints are controlled. Your global stabilisers then join in; and finally your prime movers activate, and off you go. This all happens within milliseconds and is not under your conscious control.

However, when things are not optimal – whether due to trauma such as an accident or injury, or over time through dodgy posture or chronic overuse or misuse – this beautiful harmonious sequence also goes wrong.

Local stabilisers are inhibited by pain and dysfunction, so the feedforward mechanism breaks down. They start firing late (if at all), and as a result, your joints are at risk of micro-damage from poorly-controlled movement patterns. At the same time, prime movers respond to this risk by going into spasm, because the part of your brain that responds to pain can’t tell the difference in damage between a paper cut and a broken leg: it just want to immobilise the painful area. And the global stabilisers, with their mixed function, do a bit of both!

As a result, your joints become jammed instead of stabilised, which is useful in the early stages if you really have broken your leg and need to immobilise it; but less helpful when your injury isn’t actually that severe, or if you’re at the stage of starting to heal and move!

If you’ve ever heard the term “muscle imbalance”, this is effectively what it means – muscles behaving in an inharmonious, dysfunctional way, some working too hard and others getting weak and lazy. We can actually see it on MRI scans as the local stabilisers become fatty and atrophied…

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be writing about different areas of the body that muscle balance can affect, and how you can help yourself if you’re struggling with muscle imbalances. But if you can’t wait, or if your muscle imbalance is causing pain – call us on 0207 175 0150 and we’ll be delighted to help.